Porcupine Mountains Wilderness State Park is made up of 60,000 acres of massive trees, rolling mountains, fabled shores and everlasting memories.

Also known as “the Porkies,” this western Upper Peninsula destination prides itself on the ideals of true natural, wilderness beauty and keeping Michigan’s largest state park as wild as possible.

Though a good deal of this place is a primitive area, evidence of human activity is not absent.

In fact, the Michigan Department of Natural Resources has tucked 23 rustic backcountry cabins or yurts into this stunning landscape, which are nestled into some truly beautiful spaces.

In fact, the Michigan Department of Natural Resources has tucked 23 rustic backcountry cabins or yurts into this stunning landscape, which are nestled into some truly beautiful spaces.

Upon arrival to an empty cabin, each visitor likely feels the initial excitement at the start of a new adventure.

The faint smell of woodsmoke soon wafts from the small metal stove that sits in the corner, a neat stack of dry firewood towers to its side. The scuffed wooden floor supports a few sets of bunk beds and a small, well-worn wooden table.

Somewhere in each one of these cabins there is a beaten-up old book, not the one filled with the brochures and instructions of how to navigate the park, but the one full of the first-hand history of this tiny place surrounded by so much wild.

As is the case at state parks across Michigan, the cabin logbook is somewhat of a secret treasure here at the Porcupine Mountains. Each visitor who reserves a stay in one of the cabins has the option to write his or her story.

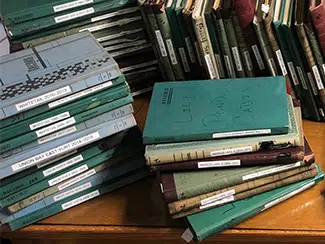

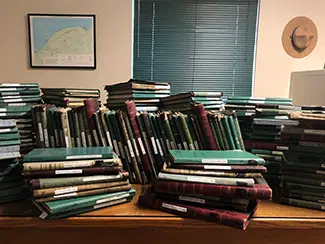

With 23 cabins and yurts across the span of 76 years, the park has gathered quite the collection of books and stories.

Within the pages of these books is the history of the park, written by the people who took the time to enjoy it.

What do complete strangers write in these books? The answer is not so simple – with so many different ages, personalities, backgrounds and viewpoints contributing, the content is broad.

A very common theme is the individual adventures – what types of critters scurried by on their hike in, what was packed for a meal or a little insight about themselves. Most stories are of good times, while others had a bit more traumatizing stay.

One entry from 1992, at the Lily Pond cabin, reads:

“We had three visitors this morning. Three very cute and comical otters were playing by the dam. I took twenty pictures and they wanted more! So, hopefully, they will come back to meet the next people. The sun is rising over the lake and it’s a beautiful morning.”

“We had three visitors this morning. Three very cute and comical otters were playing by the dam. I took twenty pictures and they wanted more! So, hopefully, they will come back to meet the next people. The sun is rising over the lake and it’s a beautiful morning.”

A visitor to the Greenstone Cabin in 1984 wrote:

“My six-month-old fell out of the backpack headfirst when my husband bent over to grab my three-year-old who was falling down the bank. Am I having a good time you ask?”

Many authors in the Porkies logbooks like to write to the strangers that will be coming in behind them. A lot of times, they give advice from experience learned or knowledge they deem worth sharing. Some authors have burning confessions, honest apologies or a simple heads-up to the next nights residents.

Some examples of the variety include:

“The wildflowers are so beautiful; be prudent in picking them. Let enough flowers stay to carry seeds and continue to keep these woods full of nature’s variety.” – Whitetail Cabin, 1991

“Sorry about the burnt popcorn smell. There’s an explanation for that. We burnt the popcorn. Expert backpackers ya’ know.” – Greenstone Cabin, 1984

“We tried some freeze-dried powdered eggs-they’re awful!! Chili-mac is great though.” – Lake of the Clouds Cabin, 2008

“I’m avoiding to tell my brother that I lost one of his spoons “tackle.” I’m notorious for decorating trees with spinners and what not.” – Greenstone Cabin, 1984

“My sister puked outside, so don’t step in it. Had some marshmallows. Very hot in here especially on the top bunks, so sleep on the bottom. Had a relaxing weekend. Went cross-country skiing a lot, saw a deer, more deer poop than deer, don’t step in that either.” – Whitetail Cabin, 1992

Humans thrive on telling tales. Many myths are started by word-of-mouth stories passed down through generations that are then put down on paper and become legends.

SI Exif

The visitors to the Porkies cabins have crafted several legends over the years.

One example is the tale of a large mouse in the Buckshot Cabin. He was fitted with the name “Grizzly Mouse, the Good Ole’ Buckshot Bear,” and he terrorized the cabin in the late 1970s.

Many visitors wrote of sightings or of hearing the mouse rustling in the night.

Others shared advice on how to outwit him to thwart his plans of stealing food or precious supplies.

“Have taken good advice of past dwellers to Buckshot. Put food under pails and pots. ‘grizzly’ won’t get your food. Then he will get discouraged and leave.” – Buckshot Cabin 1977

“Doug told Steve the legend, of the little log house. And the ferocious field varmint, named Grizzly the mouse. We slept through the night, with both terror and fright. Because Grizzly the mouse had threatened to bite.” – Buckshot Cabin 1978

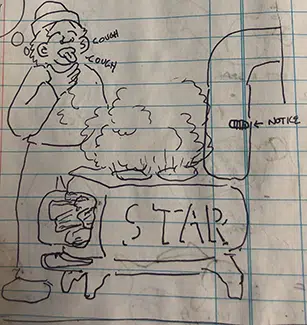

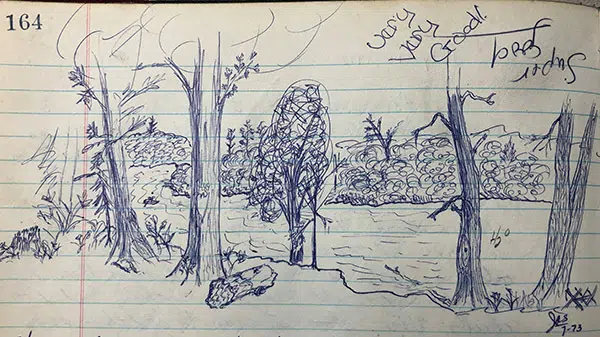

Cabin users have expressed themselves in ways other than storytelling, including poetry, music and art. Here’s a sample from the Greenstone Cabin in 1986:

“We stayed in this wilderness camp,

Without rain we didn’t get damp.

Saw no bears, it doesn’t matter,

Ate lots of food, we all got fatter.

We love it in the porcupine mountains,

too bad there aren’t more fresh-water fountains.”

A Mirror Lake two-bunk cabin visitor offered this from 1992:

A Mirror Lake two-bunk cabin visitor offered this from 1992:

“I feel fine, talkin’ bout piece of mind, I’m gonna take my time, livin’ the good life …”

Another theme running through the guest logbooks is people yelling at previous cabin renters about being slobs, critiquing each other on their backpacking methods or long entries that highlight very many rules that are broken (dogs in cabins, cutting down trees, too many people, etc.

These complaints, perhaps a precursor to today’s social media posts, date back in the logbooks as far as the 1960s.

People come from all over the world come to stay in the park’s little cabins in the woods. They come for many reasons: solitude, adventure or building bonds with family or friends.

For most cabin users through the years, there seems to be a common denominator. No matter if they were staying for a week or a single night, that empty room with a bed and a stove becomes a home.

And just like home, one is sad to go, but many leave behind the promise of return, because they’ve fallen in love with this wild, adventurous place.

A visitor to the Buckshot Cabin in 1977 summed it up nicely:

“I finally feel at ease with the world. Free from tension and anxiety. Free from all worldly pressures I must face in my everyday struggle. Yes, I have found my place; a place where I can belong. But why must I leave and when can I return?”

For more information on Porcupine Mountains Wilderness State Park, its cabins and yurts, trails and more, visit Michigan.gov/Porkies.

Comments